by Rachel Nemhauser

The room was small and cramped. My nerves were frayed. I had my hand firmly wrapped around Nate’s wrist to keep him close as I patiently waited for this new, must-see practitioner to review her notes. Desperate for an explanation for Nate’s developmental delays, extreme irritability and challenging behaviors, I lifted his squirming, four-year-old body onto the exam table. I hesitantly stepped out of the way and watched, dismayed, as the therapist pulled a very large owl feather out of her lab coat pocket and began waving it rhythmically around Nate’s face and head.

My stomach dropped and my cheeks burned. This was not going to give us answers. I felt my sorrow hit a new low as I admonished myself silently for ending up here. Another appointment that provided no answers. Another out-of-pocket expense that went nowhere. Another dead-end. I was disappointed and tired. We headed home for naptime.

*******************

When I look back, Nate’s earliest years are mostly a nervous, sleep-deprived blur. He was born when his older brother Isaac was an active preschooler. My days were usually spent attempting to function on an amount of sleep barely measurable in hours while frantically tending to the needs of two young boys. I had fantasized about being a mom for years, and could hardly wait to hold my first chubby cheeked, smiling little baby.

By the time I was in my early twenties, I craved parenthood more than a new mom craves uninterrupted sleep, and I was naively confident it would just come naturally to me. Isaac was born with colic though, and had entered our lives in a whirlwind of crying jags, speech delays and boy-energy. Instead of being idyllic and picture-perfect, our early years as a family of three had me questioning if I was even close to good enough to be his mom.

First-time parenting had hit me like a bomb. As we started thinking about adding a second child to our family, I was ready for the parenting do-over I thought I was entitled to, the one where my next child would hit all his milestones on time and have an easy-going demeanor to mirror my own.

I was completely, obsessively, head over heels in love with both my children, but after Nate arrived, I was also stressed, exhausted, short with my husband, and eager for a tropical vacation on a deserted island where I could eat meals and use the bathroom without a tiny person sitting on my lap.

Memories from that time are mostly vague and indistinct, but the emotion that lingers over all my reminiscing is a heavy, fear-laden grief. A sadness, disappointment and despair that I carried with me while I fed my kids, while I sipped coffee with friends, and while I played hide and seek in a wooded patch of our neighborhood park.

It rode in the car with me from the Little Gym to the Children’s Museum, and laid beside me at night when I tried to catch a short snooze before Nate cried for a bottle. As I kissed boo boos and played with matchbox cars and read Cat in the Hat and stirred macaroni and cheese, the grief was always there.

It’s hard to understand it now, when I look at fourteen-year-old Nate and see a complex, passionate, hysterically funny person who has a girlfriend, hobbies and a mischievous streak, but for his first few years my heart was broken.

I ached physically each time Isaac wanted his brother to play with him and Nate showed no interest.

From the very beginning it was clear that Nate had developmental delays, and I grieved as deeply for him as if I had suffered a genuine loss. For some, the idea of grieving a child who was safely snuggled in my arms may have seemed unkind, foolish, or insincere, but I felt a crushing sadness as real as if I was holding it in my hands.

I cried for every milestone he didn’t hit. I mourned every waiting room I had to sit in while a professional tried to figure him out. I grieved while I tried to learn the Special Ed system, while I tried to figure out what respite care was, and while I argued with insurance companies about therapy coverage.

I ached physically each time Isaac wanted his brother to play with him and Nate showed no interest. I felt a stab of anxiety every time I interacted with a child Nate’s age and was reminded how behind Nate really was. For Nate’s first five years, as his developmental disability gradually became noticeable, I cried and I worried and I mourned.

Of course I wasn’t only grieving, because parenting is so much more complicated than that. I had two very active boys who were counting on me, so I devoted myself to the job of raising them. It often didn’t look or feel like what I used to imagine it would look and feel like, but there were playdates, outings, birthday parties and a million other things to fill our days, and time went by. If you know Nate, you know that he kept me very busy in his early years, but also that it wasn’t even a little bit hard to fall wholly, madly, utterly in love with my curious, imaginative, trouble-making redhead.

I can’t tell you a specific moment in time, but somewhere along the way I went from fearing I didn’t have what it takes to be his mom, to wondering what I would ever do without him.

I went from thinking that his disability was “unfair” to thinking, as I watched Nate shriek ecstatically over autumn leaves being carried by a gust of wind, that I had hit the jackpot with this kid of mine.

I went from thinking I may never feel happiness again to feeling pride and bouts of mind-blowing joy while I watch my son engage with and contribute to his world.

Nate is a teenager now, and I can hardly recognize the grieving, frightened young mom I was at the beginning of his life. I have learned and grown and reflected, and although I feel regret for so much wasted worry and grief, I still feel empathy for the version of myself who felt those things.

I was wrong to see Nate’s disability as bad, as less than, as a disappointment, or as worse than I deserved; but I didn’t understand that yet. I knew very few people with an obvious disability, and I didn’t know the value, diversity, strengths and contributions people with disabilities have made to the world. I’m not proud to say it, but I had no idea.

I stopped mourning him when I started seeing him, and all people, as an endlessly unique collection of gifts, challenges, experiences and dreams.

When Nate’s disabilities emerged, seeing him catch up was my only goal, and I felt that his being “normal” would make me feel better. I thought that if I took him to enough specialists, eliminated the right foods from his diet, and consistently attended every therapy session, everything would be OK.

The problem, of course, was that he didn’t catch up, and forcing Nate to eat gluten-free bread and dairy-free cheese didn’t help anyone feel better. Dedicating myself to fixing him in order to assuage my grief was a failure. Instead, my grief only faded when I stopped seeing Nate as a series of shortcomings and started seeing him as an individual on the same spectrum of neurodiversity as everyone else I know.

The problem, of course, was that he didn’t catch up, and forcing Nate to eat gluten-free bread and dairy-free cheese didn’t help anyone feel better. Dedicating myself to fixing him in order to assuage my grief was a failure. Instead, my grief only faded when I stopped seeing Nate as a series of shortcomings and started seeing him as an individual on the same spectrum of neurodiversity as everyone else I know.

I stopped mourning him when I started seeing him, and all people, as an endlessly unique collection of gifts, challenges, experiences and dreams. I was able to move past sadness when I stopped trying to figure him out, or fix him, or mold him into a different person, and instead just adored him for exactly the individual, unbelievable, totally complete person that he is.

I wish that I could change the expectations I had held so close when I became Nate’s mom. I wish that I could go back in time to broaden my dreams of parenthood to include the potential for me to create any child, who develops at any speed, and who is comfortably settled on any spot on the spectrum of neurodiversity.

I wish I had exposures and experiences under my belt that would have strengthened my comfort level with a wider variety of people right from the start. And I wish I had known about the vibrant, diverse, important lives of the people with disabilities in my community; the activists and writers and parents and social workers and academics who contribute to our world every day. I think that knowing all of that would have enabled me to enjoy Nate’s early years in a way I ended up not being able to.

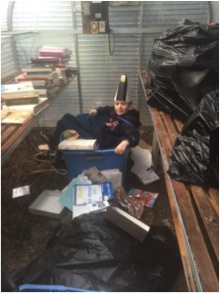

Nate is a tall, mouthy teenager now. He loves zombies, horror movies, and sneaking air kisses in the direction of his girlfriend when no one is looking.

Nate is a tall, mouthy teenager now. He loves zombies, horror movies, and sneaking air kisses in the direction of his girlfriend when no one is looking.

He’s impulsive, and although the experts say he has an intellectual disability, he’s one of the smartest and most observant people I’ve ever met.

He’s messy and complicated, and I don’t know a single other person like him.

I wasted a lot of years looking at him and feeling grief, but I’m done with that now. I’m no longer stepping out of the way while a therapist waves a feather in his direction on the slim chance it makes him hit milestones a little bit faster. Now I focus on stepping out of Nate’s way —standing back and giving him the space he needs to grow, to explore, to make mistakes, to learn, and to become the man he wants to be. It’s not always relaxing and it’s not what I expected, but it’s certainly never boring, and I can’t think of a single thing I’d rather do more.